The Favelas Through the Brazilian Rhythms of Samba and Funk

This presentation took place on February 25, 2025, at the University of Maryland, in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures.

In this presentation, I explored counter-narratives and orality as technologies of existence for Black and marginalized communities. I highlighted how these forms of expression challenge hegemonic narratives, functioning as essential strategies of resistance, memory preservation, and identity affirmation. These practices are fundamental to constructing new perspectives on the realities of historically marginalized communities, promoting a critical revision of history and the power structures that shape society.

The presentation was structured into three key moments, directly connected to my master's research:

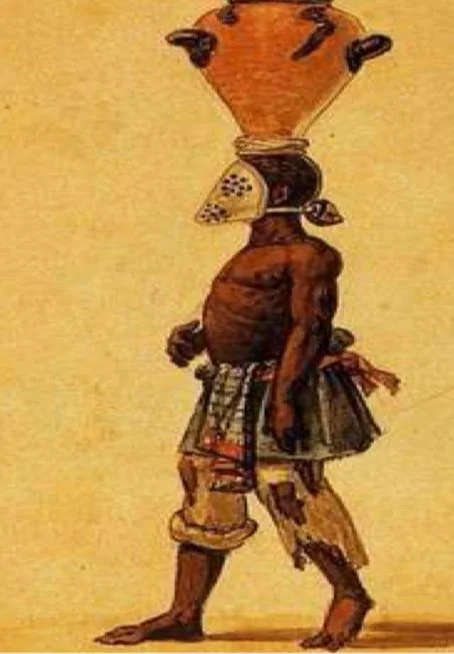

Instruments of Torture and Silence: In this first section, I examined the instruments of torture used during the period of slavery, analyzing how these devices were primarily intended to silence Black voices. This discussion is essential for understanding the historical mechanisms of oppression and the erasure of Black orality.

Samba and Funk as Voice Technologies: In the second section, I emphasized the role of samba and funk as cultural expressions that reframe orality, functioning as technological tools of voice in contemporary times. These artistic manifestations not only reinforce identity and community but also challenge the stigmas and restrictions historically imposed on Black cultural expressions.

The Relationship Between Instruments of Torture and Contemporary Black Cultures: Finally, I proposed a reflection on how torture devices and Brazilian Black cultural expressions—such as samba and funk—demonstrate the power of speech, the assertion of subjectivity, and identity affirmation in today's context. This connection reveals not only the persistence of oppressive structures but also the Black population's capacity for resistance and reinvention through art and orality.

I grew up hearing words that, to the outside world, were merely slang, deviations from the norm, or signs of supposed illiteracy. But in my lived experience, these words represent resistance and creativity, ways to name pain, joy, and challenges. The favela has always had its own dictionary, a vocabulary in constant transformation. To name is to construct a universe and create references that allow one to navigate between memories, belonging, and perspectives.

Over time, I began to reflect on how naming is also a political act, as there is an imposed standard that defines which words, stories, and knowledge are considered valid. Hegemonic narratives position people from the peripheries as mere supporting characters in their own stories, framing them within discourses that marginalize them. In Brazil, the literary canon and cultural expressions are mostly controlled by a white, upper-class, male, cis-heteronormative perspective. This model dictates what is considered legitimate in art, knowledge, and representation while silencing the experiences of Black and marginalized populations.

This silencing does not happen by chance. The epistemicide (CARNEIRO, 2023) of Black and peripheral populations has historically been justified by Catholic doctrine, for example, which, under the fallacy of the promise of salvation for the souls of the enslaved, legitimized the destruction of their knowledge and cultural expressions (MARCUSSI, 2013). One of the most violent mechanisms of this erasure was the prohibition of communication in the mother tongue among the enslaved. This strategy not only prevented the transmission of ancestral knowledge but also distorted and fragmented their cultural identities.

In this sense, Frantz Fanon (2008) argues that "the man who possesses language possesses the culture that the language expresses," highlighting how the colonization of language was a fundamental instrument of domination. Silencing a language is silencing a people, for language is not merely a means of communication but also a space of resistance, memory, and historical continuity. Thus, the imposition of colonial languages was not just a linguistic displacement; it was a strategy of identity rupture, a means of dismantling community ties, and consolidating a system of oppression that persists to this day.

The process of domination through language can be observed in different colonial contexts. Fanon (2008) discusses the imposition of French in Martinique by colonizers in 1635, demonstrating how the suppression of the mother tongue distanced colonized people from their cultural and epistemological references. In Brazil, where colonization began around 1500, a similar linguistic and cultural erasure took place. Enslaved people, forced to express themselves in the colonizer’s language, not only lost a means of communication but were also deprived of the symbolic universe and meanings that their mother tongue provided.

DEBRET, Jean-Baptiste. Escravizado com máscara de flandres. 1835.

Gabriel Nascimento (2019), in discussing linguistic racism, emphasizes how the Black population was systematically categorized and subordinated through language. Forced to adopt the colonizers' language as the only legitimate form of expression, their original languages were marginalized, and consequently, their experiences and histories were silenced. Thus, linguistic imposition became a tool for controlling not just words but also the very voice and power of speech of the Black population, reinforcing social hierarchy and colonial oppression.

However, language also became a space of resistance. For the enslaved, communication went beyond the mere exchange of words: it enabled the creation of codes, symbolic forms of struggle, and survival. Orality, often devalued in relation to writing, must be understood as a technology for knowledge production and identity construction. In contexts of subordination, such as that of the enslaved Black population, orality not only preserved and transmitted histories but also resisted the discourses that sought to silence these experiences.

Thus, throughout history, language has been both an instrument of domination and a tool of liberation. While power systems impose norms and standards that seek to delegitimize peripheral and Black expressions, marginalized populations recreate language, transforming it into a space of affirmation, memory, and resistance.

As bell hooks (2019) points out, power operates as a mechanism that hinders freedom, but within any structure of domination, there are always spaces of resistance.

Currently, oral counter-narratives gain relevance by challenging official versions and occupying spaces of speech that have historically been denied. By serving as tools that amplify voices and lived experiences, orality transforms silencing into affirmation, contributing to the redistribution of power in dominant narratives.

All of this is because, in Brazil, Black and peripheral communities have been targets of stereotypes that distort their realities and experiences. These stereotypes, largely originating from colonial accounts, continue to be perpetuated by a Eurocentric and prejudiced perspective. The scarcity of authentic records about the lives of Black populations has reinforced this distortion, erasing their identities and real histories.

These stereotypes function as mechanisms of control, naturalizing inequalities and justifying oppression. As Collins (2019) argues, controlling images reinforce the idea that the subordinate position of Black people is inevitable, consolidating racism, poverty, and other forms of inequality as part of the natural order of things.

In the context of Black culture, samba and funk represent much more than mere forms of communication—they are affirmations of identity and resistance. These cultural manifestations position Black people as active subjects in the construction of their own narrative.

Samba, for instance, created a new language that expresses not only culture but also the struggle for survival and the preservation of collective memory. Although constantly reinvented, it maintains its roots in the manifestations of the popular and Black classes. As Diniz (2006) highlights, "samba spread across the national territory with the symbols of Black culture" and has always been the voice of the peripheries, facing resistance from the elites.

The formation of Brazilian identity, as Munanga (2008) points out, was marked by eugenic strategies that sought to promote a white image of the nation. In this process, the contributions of Black populations were ignored, and their participation in the construction of the country was erased from official historiography.

Music, as a form of cultural expression, has always played a fundamental role in resistance and in affirming the identity of historically marginalized groups, such as Black and peripheral communities in Brazil. Within this context, samba and funk emerge as forms of counter-narrative, playing a crucial role in transmitting collective memories and constructing an autonomous sense of being, based on the knowledge of their culture.

During Carnival, the samba-enredo is one of the most remarkable expressions of this resistance. The samba-enredo "Chico Rei" (1965) by the Salgueiro samba school, for example, revives the story of the legendary African leader who was brought to Brazil as an enslaved person and, through his struggle, achieved freedom and leadership. This samba not only moved the audience but also exalted the power and contribution of Black people in building the country. Other sambas, such as "Cangoma me Chamou" (1970) by Clementina de Jesus and "Sorriso Negro" (1981) by Dona Ivone Lara, address Black resistance, singing about identity, beauty, suffering, and the struggle for the affirmation of Black people.

Clementina de Jesus

Still within the context of samba, Azevedo (2006) highlights that, in the early 20th century, samba gatherings were characterized by orality and the repetition of lyrics, as many participants were illiterate. This system of repetition, though simple, served to fix the songs in collective memory. In this way, orality became an essential element of preservation and resistance, keeping alive the memory of a culture that continues to claim its space and voice.

Today, samba remains one of the main forms of cultural resistance. Alongside it, however, funk has also emerged as a powerful expression of resistance and affirmation of Black and peripheral identity. Both funk and hip-hop share characteristics of struggle and resistance against social inequalities, giving voice to historically marginalized populations.

Funk, originating in the outskirts of large cities, especially in favelas, directly reflects the experiences of its creators. Its lyrics address themes such as identity, inequality, freedom of expression, and the fight against oppressive systems. Thus, orality becomes a central tool in the pursuit of epistemic justice and social recognition. As Patrícia Hill Collins (2019) points out, the lived experiences of these groups carry essential knowledge, fundamental for constructing new ways of understanding the world.

In many ways, funk is a cry of resistance, especially among Black youth in the favelas, who use music to challenge stereotypes, affirm their identity, and seek visibility in Brazil’s political and cultural landscape. However, as often happens with cultural expressions originating from the periphery, funk faces criminalization and attacks—both symbolic and physical—in a constant attempt to control and marginalize it.

More than just a musical genre, funk is a reflection of ongoing struggle and a way of expressing what is often silenced by society. Since the 1980s, Brazil has undergone significant political changes, and funk has been part of this history, narrating the country's events in a context where popular culture and peripheral manifestations often lack state support.

The state does not encourage the funk movement because there is no interest in recognizing the cultural expression of historically marginalized groups. Power structures do not view favorably the possibility that these people could construct and express their own discourse, as this could challenge and destabilize the existing social order. As Collins (2019, p. 146) points out, stereotyping can be understood as the creation of "controlling images," that is, representations designed to make racism, sexism, poverty, and other forms of inequality appear natural, normal, and inevitable in everyday life. These images, when widely disseminated and accepted, not only legitimize oppression and social exclusion but also reinforce the belief that the subordinate position of certain groups is unchangeable. Thus, stereotypes are not merely misperceptions but ideological tools that sustain and perpetuate inequalities, ensuring the maintenance of power hierarchies in society.

Funk, in its essence, challenges established norms and, in doing so, carries the energy and voice of a generation that refuses to be subdued. The song Som de Preto by the duo Amilcka and Chocolate clearly expresses this resistance: "It’s the sound of Black people, of favela dwellers, but when it plays, no one stands still. Our sound has no age, no race, and no color, but society doesn’t value us, they only want to criticize us, they think we are animals."

Since the first street parties in the 1990s, funk has been a genre that blends various rhythms, such as soul and Black music, prevailing in Brazil’s favelas. Its aesthetics, often considered chaotic, actually reflect the vibrant energy of the peripheries, which, despite marginalization, continue to produce culture in an irreverent and powerful way. Funk, therefore, emerges to challenge the system and the official narrative, giving life to those who are constantly forgotten.

Acervo: Fernanda Souza/ Correrua

By criminalizing these expressions, the state attempts to erase the power of funk and the cultural resistance of the peripheries. However, the rhythms of funk parties and the energy of the music ensure that, even in the face of marginalization, people feel alive, affirming their presence, resistance, and struggle with every beat.

Funk deeply connects with young people, especially those from the periphery, as it reflects their daily experiences and struggles. The identification with its lyrics is undeniable, as the genre brings to light the aspirations, challenges, and desires of a population neglected by the state. In this way, funk stands as one of the greatest political and cultural movements of today, as it speaks directly to those who have historically been marginalized and silenced by structures of power.

Funk is not limited to partying and celebration; it asserts itself as a form of resistance that exalts life and Black culture, highlighting its capacity to create and subvert within an oppressive system. The simple act of dancing at funk parties is capable of challenging rigid structures, affirming the right to space and cultural production.

This transition from oppression to identity affirmation can be seen as an inversion of the narrative of silencing. If Black bodies were once silenced by torture and violence, music—whether samba, funk, or hip-hop—now becomes a tool of reconstruction, active voice, and affirmation of power. The presence and expression of Black people in contemporary society transcend a mere response to a past of subjugation; they are the seed of a future where their existence not only resists but flourishes.

The funk movement, like samba, carries within it the power to decolonize language. While mechanisms of oppression tried to diminish Black speech and cultural expressions, this very speech became a tool of freedom. Funk, like samba before it, surpasses the limits of normative grammar and enters the realm of creation and resistance. It is a manifestation of identity that reclaims orality. It is not just about demanding space but affirming, with strength and dignity, that its history, culture, and identity are the foundations of a future built on struggle, art, and memory.

Samba and funk, as examples of cultural resistance, show how orality, even historically controlled, is a tool of resilience and struggle. The "good speech"— the one that asserts itself as a subject of knowledge, history, and culture—is the one that refuses to be silenced. Unlike the silence imposed by centuries of oppression, the "good speech" asserts itself and reaffirms, breaking the linguistic and cultural barriers of control that sought to subject the Black population to oblivion.

For all these reasons, it is essential that we speak, that our voices be heard. Funk, samba, and so many other cultural expressions are not just forms of entertainment but of affirmation and resistance. They show us that Black culture is alive, powerful, and impossible to silence. Therefore, let us speak, let us continue to occupy spaces, celebrating our history, our identity, and our struggle for dignity.

Resonances of the Drum: Between Roots, Resistance, and Memories

Baltimore, 2025. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal.

The drums, as instruments of great cultural significance, play a profound historical role in resistance and communication, especially in times of repression, struggle, and celebration. In various parts of the world, such as in colonial Brazil, drums were used as a means of communication among the enslaved, enabling the organization of escapes and revolts, while also strengthening the movement of resistance against oppression. For this reason, during many periods, both in the United States and Brazil, between the 18th and 19th centuries, drums were prohibited, as they were seen as a threat to colonial and imperial authorities, who feared their power to unite and mobilize the oppressed.

Eubie Blake National Jazz and Cultural Center, 2024. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal.

The prohibition of drums, particularly in contexts of slavery, reflects not only an attempt to neutralize resistance but also a desire to suppress African and Afro-Brazilian cultures. The sound of the drum, imbued with strong symbolism, was an expression of the identity and spirituality of the subjugated peoples; thus, its repression aimed at social and cultural control. However, despite these prohibitions, the drum never ceased to be a powerful tool of resistance and a form of cultural preservation, as evidenced by the rhythms and musical styles that emerged, such as samba, candomblé, and funk.

Walking through the streets of Baltimore...

Edges of Ailey Exhibition at the Whitney Museum, 2024. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal.

Drums manifest in various forms, not only as sound instruments but also as visual and cultural symbols that mark the urban landscape. It is common to see representations of drums painted on the walls of buildings, reflecting the presence and importance of this tradition, not necessarily in the city itself, but in its diasporic roots. Moreover, drums occupy space in studios and workshops, keeping alive the connection between people and the historical and cultural roots they represent. In galleries and exhibitions, drums also appear in paintings, reinterpreted by local and immigrant artists who explore the symbolism and aesthetics of these instruments in a contemporary context.

Baltimore, 2024. Fonte: Arquivo pessoal.

These drums, both in their physical form and in artistic representations, have guided encounters and dialogues, becoming a point of convergence for people who seek to preserve and strengthen cultural traditions. Yet more than that, sometimes, without searching for them, people find the drums through ears, eyes, and bodies that need to feel their presence. In Baltimore, it has not been uncommon for the sound of the drum or its vibrant image on the city walls to become the center of new connections and moments of communal sharing. In this way, the drums continue to be a constant and guiding presence, conveying stories of resistance and identity, and creating spaces where culture and history meet and renew with every encounter.

Baltimore, 2025. Fonte: Arquivo Pessoal.

The drum, in this cycle between past, present, and future, becomes a point of connection between what we were, what we are, and what we can be. In Brazil, its relationship with the people goes beyond being a mere instrument; it is a living memory that carries the stories, struggles, and feelings of a people. Whether in samba circles, popular festivals, or cultural manifestations, the drum has always been present, marking both presence and memory.

Here in Baltimore, the experience with the drum takes on a different form, yet still retains the strength of a link to its roots. The beats continue to echo, now in another context, but with the same power to connect us to what is essential. The drum, both in Brazil and here, teaches that looking to the past is not an escape, but a way of understanding the present and what is still to come.

Whispers Between Two Worlds: Welcome

Welcome to the space where the experiences of Brazil in Baltimore meet the emotions of writing. This blog is born from the desire to record, in an intimate and sensitive way, the everyday experiences that bridge two cultures—between the warmth of the homeland and the unique climate of this American city. Here, words will serve as the thread guiding a journey that unfolds in the simple yet profound gestures of daily life: spontaneous conversations with strangers, strolls through museums that breathe history, visits to restaurants that reveal flavors and feelings, attentive listening at bus stops, footsteps echoing in parks, small rituals in cafés and markets, reading signs that translate a foreign reality, and even moments of introspection that a cold day can bring. Alongside each story, I aim to give life to a distant, yet always present, Brazil, and a Baltimore that gradually becomes familiar. May this space thus become an invitation for reflection and the sharing of the small, great stories that shape everyday life.